September was a busy month for Australia’s evolving climate reporting landscape. With the first mandatory disclosures under AASB S2 Climate-related Financial Disclosures due from 1 January 2025, regulators and standard-setters spent the month issuing guidance, educational materials and reminders to help companies and auditors get ready.

Below is a concise recap of what changed or was clarified in September 2025—and what it means for reporting entities as the regime moves from policy to practice.

1. AASB guidance on proportionality: scaling S2 for smaller entities

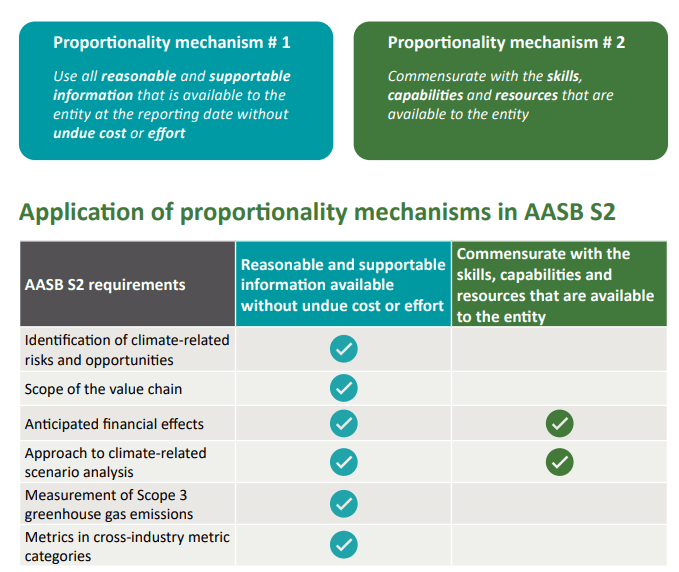

On 9 September 2025, the Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) released guidance explaining how the “proportionality mechanism” in AASB S2 should work.

The document outlines how entities can apply judgement to make their disclosures commensurate with size, complexity and climate exposure.

The message is clear: the standard applies to everyone in scope, but not every disclosure needs to look the same. Smaller or less complex entities may use simplified scenario analysis or more qualitative data—so long as they still meet S2’s disclosure objectives.

For practitioners, this guidance provides welcome clarity. It reinforces that “one size fits all” reporting was never the intent. Instead, scalability is built in, supporting the phased rollout for Group 2 and Group 3 reporters in 2026–27.

📘 Source: AASB Proportionality Mechanism in AASB S2 (9 Sept 2025).

2. Educational material on greenhouse gas (GHG) disclosures

Earlier in the month, the AASB issued educational guidance on GHG emissions disclosure under S2 (2 September 2025).

This resource supports preparers facing the technical challenge of measuring and reporting emissions consistently with S2 and the Greenhouse Gas Protocol.

Key themes include:

- Clarification of Scope 1, 2 and 3 boundaries (Scope 3 required from year two).

- Emphasis on credible measurement methods and estimation techniques where data gaps exist.

- Alignment between NGER data (for entities already reporting under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act) and the numbers disclosed in the financial report.

- Encouragement to reference industry-based metrics (e.g. SASB or ISSB guidance) where relevant.

The AASB also reiterated the transition relief on Scope 3 emissions: companies must describe their approach in year one but only disclose figures in year two.

For auditors, this educational material is equally valuable—it clarifies what constitutes acceptable methodology and estimation uncertainty for assurance planning.

📘 Source: AASB Educational Material on GHG Disclosures (2 Sept 2025).

3. Implementation reminders, liability relief and director attestations

Reinforcing the 2025 start date

By September, Group 1 entities (large listed and financial sector companies) were entering final preparation mode.

ASIC publicly reiterated that it expects “full, true and fair” climate disclosures aligned with AASB S2—and warned against selective reporting where risks appear in investor presentations but not in statutory reports.

No new regulatory guide was issued, but ASIC’s long-standing RG 247 is effectively superseded by S2.

“Modified liability” now in force

A major September talking point was the temporary safe harbour protecting companies and directors from private litigation over forward-looking climate information—such as Scope 3 estimates, scenario analysis or transition plans—provided statements are made in good faith.

The shield runs until 31 December 2027, though ASIC retains enforcement powers. The aim is to encourage frank, early disclosure while the market gains experience.

Director declarations

For the first three years, boards need only declare that they have “taken reasonable steps to ensure compliance” rather than that the Sustainability Report gives a “true and fair view.”

This lighter attestation acknowledges that climate reporting is new territory while still demanding documented governance oversight.

📘 Sources: Treasury Laws Amendment (Climate-related Financial Disclosures) Act 2024, ASIC climate reporting resources.

4. Progress on assurance standards

While no new assurance standard was finalised in September, the AUASB continued work on ASSA 5010, complementing ASSA 5000 (already approved earlier in 2025).

Audit firms are now developing methodologies for limited assurance on climate disclosures for FY 2025 reports.

Across the profession, pilot engagements and training programs ramped up—particularly within public-sector audit offices and major accounting networks. Even where assurance is not mandatory this year, many entities are seeking voluntary reviews to enhance credibility ahead of investor scrutiny.

📘 Source: AUASB Sustainability Assurance Developments.

5. Sector-specific observations

No new sector exemptions or amendments were released, but regulators used September to reinforce expectations:

- Financial institutions should be leaders in Scope 3 “financed emissions” reporting and scenario analysis for credit and investment portfolios. APRA’s Climate Vulnerability Assessment complements S2 objectives.

- Energy and resources entities must integrate NGER emissions and TCFD-style scenario work directly into financial statements. ASIC has signalled it will look for consistency between climate disclosures and asset valuations.

- Manufacturing and industrials should pay attention to proportionality guidance—qualitative disclosures may be acceptable initially, but planning for quantitative data is essential.

- Real estate and agriculture are expected to highlight exposure to physical climate risks (e.g. floods, heat, drought) in line with S2’s risk-management pillar.

Practical next steps for accountants and auditors

1. Finalise readiness for FY 2025 reports.

Ensure draft Sustainability Reports align with AASB S2’s structure—governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics/targets. Use the AASB Knowledge Hub as a checklist.

2. Apply proportionality wisely.

Smaller entities can scale disclosures but should still cover every major requirement qualitatively. Document the rationale for lighter treatment to show compliance intent.

3. Strengthen board engagement.

Directors must demonstrate those “reasonable steps.” Keep minutes, training records and climate discussions well documented for audit evidence.

4. Prepare for assurance—even if limited.

Gather calculation workbooks, emission factors, scenario models and control documentation early. These will support both internal review and external assurance under ASSA 5000.

5. Monitor for further updates.

Expect more FAQs and examples from Treasury, ASIC, and the professional bodies as Group 1 entities begin publishing.

The bottom line

By the end of September 2025, the climate-reporting framework in Australia had moved firmly from rule-making to implementation.

The AASB provided practical tools, the AUASB advanced assurance infrastructure, and regulators made clear that high-quality disclosure—not mere compliance—will be the expectation.

For preparers and auditors, this is the last stretch before go-live. Those who embrace the AASB’s September guidance on proportionality, emissions measurement and director accountability will be best positioned to produce credible, decision-useful climate information in 2025 and beyond.

Further reading